I used to dread negotiations. Whether it was discussing project scope with a client, asking for a raise, or even deciding on a team deadline, my approach was always the same: figure out what I wanted, dig my heels in, and prepare for a battle of wills. Sometimes I “won,” leaving the other side feeling resentful. Sometimes I “lost,” leaving me feeling frustrated. More often than not, we both walked away feeling exhausted and dissatisfied, having damaged our relationship in the process. My negotiations were not collaborations; they were confrontations.

I thought this was just how negotiation worked. It was a zero sum game, a tug of war where one side’s gain was the other side’s loss. I assumed being effective meant being tough, being positional, and giving as little ground as possible.

Then I read Getting to Yes by Roger Fisher and William Ury, and it fundamentally changed my entire understanding of negotiation. The book introduced a concept called principled negotiation, a radically different approach focused not on winning a battle, but on solving a problem together. It provided a simple, powerful, four step method that transformed my negotiations from stressful confrontations into productive collaborations. It did not just make me a better negotiator; it made me a better leader.

The Problem: Why Most Negotiations Fail (The Trap of Positional Bargaining)

Table of Contents

The approach I used to take is called positional bargaining. It is the default for most of us. It involves:

- Starting with an extreme position (e.g., asking for a huge budget).

- Slowly making concessions.

- Meeting somewhere in the middle, usually resulting in a compromise that leaves neither side fully satisfied.

This approach is deeply flawed because:

- It damages relationships: It frames the negotiation as a contest between adversaries.

- It is inefficient: It involves a lot of posturing and time consuming haggling.

- It often leads to suboptimal outcomes: By focusing only on the stated positions, it misses opportunities for creative solutions that could benefit both sides.

- It rewards stubbornness: The person who is most willing to be unreasonable often “wins.”

If your negotiations feel like a tug of war, you are likely trapped in positional bargaining.

Also read: Stop the Workplace Tug of War: Win More With These Negotiation Tips!

A Better Way: Introducing Principled Negotiation from Getting to Yes

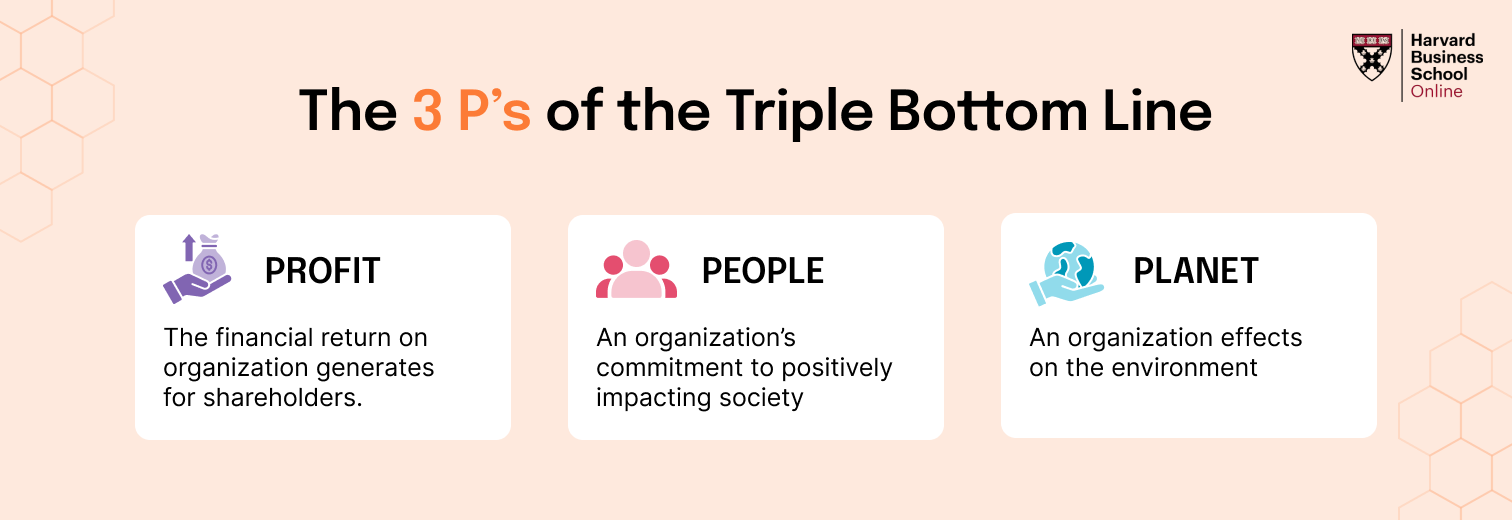

Principled negotiation, developed by the Harvard Negotiation Project, offers a different path. It is an interest based approach designed to produce wise outcomes efficiently and amicably. Instead of focusing on winning your position, you focus on satisfying the underlying interests of both parties. It is a shift from win lose to win win. This method is built on four core principles.

The 4 Principles Playbook

Principle 1: Separate the People from the Problem

Positional bargaining puts the relationship and the substance of the negotiation in direct conflict. Principled negotiation addresses them separately. Recognize that the people on the other side have emotions, values, and perspectives, just like you. Deal with “people problems” directly through empathy, clear communication, and active listening, without making concessions on the substance.

- Workplace Example: Your colleague is consistently late delivering their part of a project (the problem). Instead of attacking their character (“You are unreliable!”), focus on the issue and collaborate on a solution. “I understand you have a lot on your plate (empathy). However, when your report is late (problem), it delays our entire team’s timeline. Can we talk about how we can ensure this gets done on time next week? (collaboration).”

Also read: How to manage people who dislike each other

Principle 2: Focus on Interests, Not Positions

A position is what someone says they want (“I need a 10% raise”). An interest is the underlying need or motivation behind that position (“I need to feel my contributions are valued and fairly compensated compared to the market”). Positional bargaining focuses only on the stated positions. Principled negotiation digs deeper to uncover the underlying interests of both sides. Often, seemingly conflicting positions are driven by compatible interests.

- Workplace Example: Two departments are fighting over budget allocation (positions). Instead of just haggling over the numbers, explore their underlying interests. Department A might need funding for a critical compliance project (interest: avoiding risk). Department B might need funding for an innovative experiment (interest: driving future growth). Understanding these interests opens the door to finding solutions that satisfy both needs, rather than just splitting the difference on the budget.

Principle 3: Invent Options for Mutual Gain

Once you understand both sides’ interests, you can move beyond the assumption that there is a single “fixed pie” to be divided. The goal here is to brainstorm creative solutions that make the pie bigger. Dedicate time specifically to inventing options before evaluating them. Separate the act of creating ideas from the act of judging them. Look for solutions where differences in interests can actually lead to compatible trades.

- Workplace Example: You want a promotion (interest: career growth, more impact), but your boss cannot give you the title change right now (constraint). Instead of getting stuck, invent options. Could you take the lead on a high visibility project? Could you get a formal mentorship from a senior leader? Could you receive a specific training budget? Look for ways to satisfy your underlying interests even if the initial position is not immediately possible.

Also read: 11 Ways to Unleash Creativity and Innovation

Principle 4: Insist on Using Objective Criteria

When interests conflict, avoid resolving the dispute based on a battle of wills. Instead, base the decision on fair, objective criteria that are independent of either side’s preference. This could be market data, industry standards, legal precedent, or scientific evidence. Using objective criteria makes the negotiation feel more like a joint search for a fair solution, rather than a personal contest.

- Workplace Example: You and a colleague disagree on the best technical approach for a project. Instead of arguing based on opinion (“My way is better!”), agree on objective criteria to evaluate the options. Which approach is more scalable according to industry benchmarks? Which has better long term maintainability based on expert analysis? Which aligns better with documented security standards? Let the data, not the egos, drive the decision.

Your Power Source: Understanding Your BATNA

What if the other side is more powerful or refuses to play by these principles? Your power in any negotiation comes from your BATNA: Best Alternative To a Negotiated Agreement. Before you even start negotiating, you must know what you will do if you cannot reach an agreement. What is your walk away alternative? Knowing your BATNA protects you from accepting a bad deal out of desperation and gives you the confidence to insist on a principled approach.

Effective, Not Just Nice

Learning the principles from Getting to Yes was a game changer for me. It taught me that negotiation does not have to be a stressful battle that damages relationships. It can be a collaborative process of problem solving that leads to better outcomes for everyone involved.

Principled negotiation is not about being “nice” or “soft.” It is about being effective. It is a strategic, disciplined approach that replaces the inefficiency and animosity of positional bargaining with the creativity and mutual respect of interest based problem solving. It is the foundation for building stronger agreements and stronger relationships, one conversation at a time.

If you are looking to equip your team with the skills to negotiate more effectively and build stronger partnerships, explore FocusU’s programs on communication and collaboration.